The new edition of Works in Progress is out. It's got a few things that are worth a look (e.g.,

Samuel Hughes on architecture) but I just want to talk a little bit about

this one, on the Baby Boom. (I recommend that you read it - it is well done and interesting - but you'll get the important bits from my summary below.)

Long story short: today, as we all know, birth rates are collapsing and no solution is in sight; but we (i.e., the West) were in this position before, in about 1930, and the problem then was solved by the Baby Boom; now, you might think that the Boom was something to do with the end of WWII, but it wasn't - it started earlier and it happened in neutral countries and ones well away from the war just as it did in the US and UK. So: why did the Baby Boom happen? And can we repeat it?

The authors come to the conclusion that three factors made a difference: "advances in household technology, progress in medical technology, and easier access to housing".

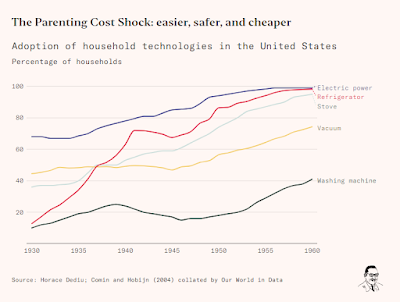

I'm completely unconvinced by the first one: the authors take the clever step of looking at the Amish (i.e. people unaffected by advances in household technology) and point out that they had a baby boom too. Moreover, their evidence of increased adoption of household technology is (a) US-centric (i.e., failing to account for the worldwide effect) and (b) underwhelming for the period we are interested in, namely c.1935 to c.1955, when the only marked change seemed to be in fridges.

As for the last of the three factors - housing - well, we expect to see housing come up in any modern discussion of progress; I suspect that I have said more than enough on the topic recently. For present purposes, let me just say that I would have liked to know more about Amish housing.

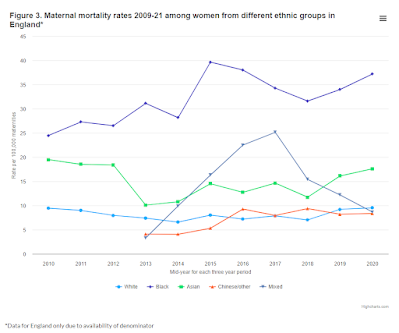

But what about the second factor - progress in medical technology? By this, the authors mean in particular improvements in peri-natal care. The collapse in maternal mortality during this period is indeed heartening and remarkable: there's a great graph at the link that I'll let you look at for yourself. It does seem to have made a difference: for example, the Amish use modern medicine, so they benefitted from these improvements too.

So, what's the situation now? Getting worse in the US:

Not looking too good in the UK either:

Comparable data for France is harder to get (blame my English-language Googling and laziness), but infant mortality is not going well:

I tried Germany next and found the more useful and general information that the UN and WHO have

released a report called “Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2020”, using national data on maternal mortality from 2000 to 2020 that finds that "

progress in some countries [in Europe] slowed down or stopped between 2016 and 2020". I've checked the report and it seems to indicate that things have been getting worse in Europe and North America since 2016.

The

Gates Foundation has some user-friendly graphs to similar effect. Here is the one for "high income" countries - as you can see, not a happy story.

This is a disgrace, isn't it? Forget about fertility rates for a moment: hardly a week goes by without some great advance in medical science being widely reported - and not just some splashy headline but a real matter of importance to public health (remember covid vaccines?) - and yet maternal mortality is getting worse? What the actual?

Of course - thankfully - the absolute numbers of deaths are still very low. But mortality rates must be the tip of the iceberg: for every mother or infant who dies, there must be many more who come close, which must be very upsetting to everyone concerned and hardly conducive to anyone wanting to repeat the experience. Indeed, anecdotally, birth experiences that involve horrendous loss of blood and medical emergencies are not at all uncommon. That's frankly a bit rubbish for a well-understood, natural process undergone, at a reasonably predictable point in time, by women of (necessarily) childbearing age all of whom are (necessarily) sufficiently healthy to have become pregnant in the first place. One does not have to be a terribly radical feminist to suspect that the brightest and best in the field of medical research are not spending their time on women's issues.

Moreover, horrible scares and serious injuries must surely be the tip of an even larger iceberg, namely generally poor experiences for women in childbirth. Perhaps the story goes a bit like this: in the 1930s, 40s and 50s, new mothers would tend to see shiny new hospitals and wonderful new medical techniques, and they would be impressed; their own mothers would say "it wasn't as nice as this in my day"; their husbands would be confident that they were in good hands; they would come out of the childbirth experience with a feeling that things were on the up and that, if they needed to give birth again, they would be able to do so in decent (perhaps even better) circumstances; and they would tell their friends the good news. But, even if the overall quality of care is better now than in the 1950s, the subjective experience, compared with the expectations that we have for healthcare as a whole, is worse; and the objective measures of quality seem to be going in the wrong direction. How many mothers now come away from giving birth once and say "well, I'm not going through that again"?; how many fathers say "I wouldn't ask you to go through that again"?; how many women hear awful stories from their friends and decide that discretion is the better part of valour? Enough, I suspect, to make at least some difference to the overall birth rate.

As I say, even if you have no interest in the long-term future of the human race, you should at least be appalled to see standard medical care in rich countries getting worse. What to do? I thought that I might give some money to a charity that does research in the field. So I went to the website of the British Maternal and Fetal Medicine Society (seemed a sensible place to look) and looked at their

charities page. A bit odd: a cystic fibrosis charity, a charity devoted to "

promot[ing] the scientific study, both pure and applied, of all psychological and behavioural matters related to human reproduction", a charity for premature babies in Northern Ireland and a charity "

dedicated to improving the quality of life for seriously ill and injured pregnant women, children and babies in countries where there is extreme poverty" (looks good, but I went to their website and they have no news since 2019, so don't look too active). None looking at improving medical care in the delivery of babies.

Save the Children has a page on

maternal and reproductive health, which starts with an emphasis on preventing women becoming pregnant too young. DFID seems to have adopted a similar approach, but the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (a UK agency that scrutinises whether overseas aid is spent effectively) is

unimpressed by the results. I suspect that's the Gates Foundation's approach as well. Not what I wanted: I was looking to try to improve the experience of giving birth, not avoid it.

Anyway, the best I came up with is this:

UCLH has a women's health and maternity fund that carries out these tasks (note research in the second bullet point).

The

research itself looks like the right kind of thing: "

Investigate the role of T-regulatory (Treg) cell in maintaining a healthy pregnancy and influencing the development of pre-eclampsia", "

improve the quality of imaging from Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and ultrasound and use these to develop low risk techniques for diagnosis, treatment and therapy for a range of dangerous conditions of the baby during pregnancy" and all kinds of medical stuff I don't pretend to understand.

So I gave them some money. Perhaps I have helped invest in the future of the human race; I hope so. But maybe it will just help a bereaved parent spend some time away from the sound of new-born babies; I'd be happy with that too.